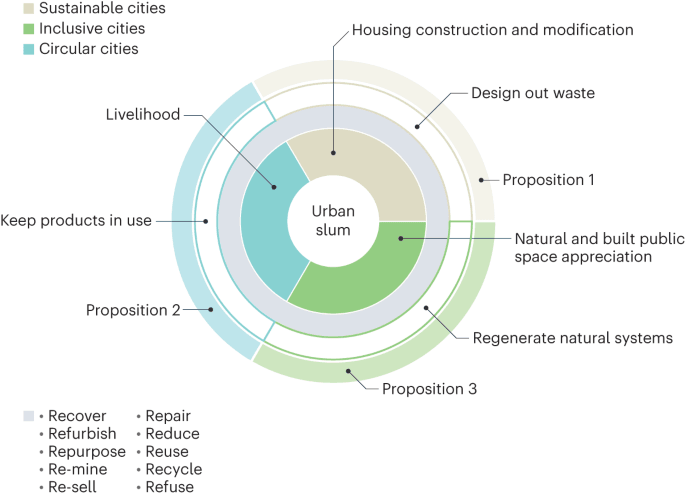

Research into these issues is already uncovering many policy solutions that could lead to resilient, inclusive, sustainable societies. There is the circular economy, for instance, where the full life cycle cost of goods and materials is factored into prices, and where the by-products and waste from one process become the feedstocks for others.1 Sustainable economic policies must also deal with the externalities of climate change, which lead to forced migration, with all kinds of consequences on the societies at the origin and the destination, and agriculture through altered environmental conditions. Our societies also have to solve issues of globalisation, and of automation and employment before they cause significant economic changes that can lead to social unrest. Many of the required economic models and measures have been invented, but are yet to be implemented.

SELECTION OF GESDA BEST READS AND KEY REPORTS:

In January 2023, two researchers from Pennsylvania State University delved into the potential of major oil conglomerates in leading the charge against climate externalities. How Big Oil Can Internalize Climate Change Externalities suggested an industry-centric approach for escalating green investments, emphasising their vital role in offsetting climate impacts. In July, Australian and US researchers published Advancing a slum–circular economy model for sustainability transition in cities of the Global South, offering a fresh perspective on the circular economy's role within Global South's slums, and advocating for the reconceptualisation of slums as springboards for urban sustainability. On the technological front, a collaboration between UK and Nigerian researchers published Human-Robot Co-working Improvement via Revolutionary Automation and Robotic Technologies – An overview. This charts the new horizons of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, spotlighting cutting-edge automation technologies tailored to enhance and streamline human-robot synergy.