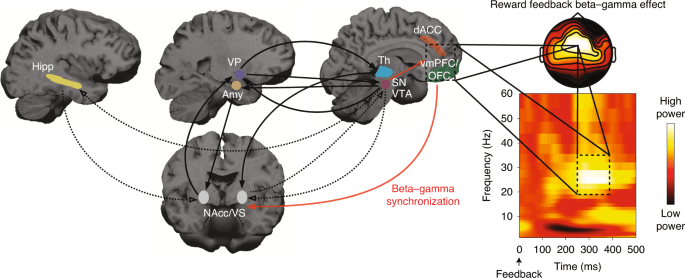

Big data approaches to increasing amounts of raw brain data will enable researchers to decode cognitive and emotional states and to elucidate fundamental principles of cognition and memory.10 Machine learning has implications for neural decoding, including determination of the neural correlates of memory encoding, retention, and retrieval.11 This approach already decoded word formation at an unprecedented rate of 62 words per minute.12

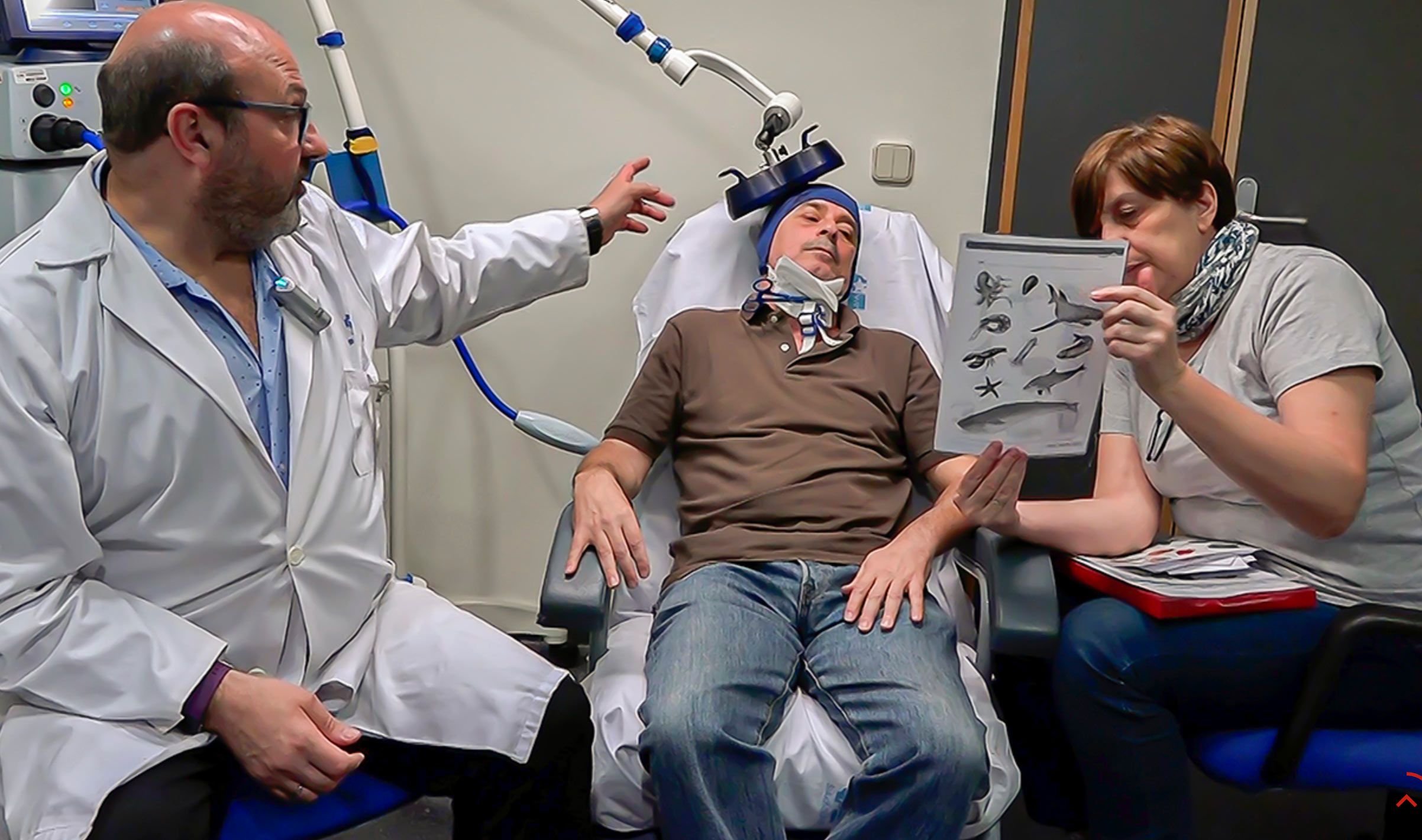

The rise of predictive large language models means semantic decoding becomes possible even without brain implants; one has decoded continuous language from fMRI.13 This progress suggests that even non-invasive brain recording devices could eventually improve enough to be wearable, reliable and affordable, paving the way for non-medical uses such as employee monitoring.