Now the psychedelic revolution is starting up again. A decade ago the authors conducted the first neuroimaging examination of LSD’s effects in the brains of healthy volunteers. Since the publication of this landmark study,1 the field has expanded from a few labs examining an exotic topic in neuroscience into an extensive network of academic laboratories and dedicated university centres in prestigious institutions. This work is being conducted around the world but is concentrated within the UK, USA, Switzerland, Spain and Brazil. In June 2023, the largest ever conference on the topic, Psychedelic Science 2023, took place in Denver, Colorado, USA, with about 500 speakers and 12 thousand participants from many countries.

Given that most psychedelic substances remain controlled, some might find these developments surprising, and perhaps concerning. But consider the need. Mental health is considered by the World Health Organization to be our biggest challenge. But most countries invest less than they should in the field, and the unmet need is huge. Psychedelics are powerful agents which target specific receptors in the human neocortex and can dramatically affect cognitive functions and emotions for a period of a few minutes to many hours. This makes their use quite distinct from almost any medication in current use in psychiatry.

Research with psychedelics has therefore mostly focused on their psychiatric applications. Although such research has been ignored by funding agencies for a long time, it has continued to evolve for decades through the visionary actions of philanthropic donors. At the beginning of the 2020s this evolved into a growing drug development marketplace, with a few specialized investment funds and hundreds of startups, plus a few public companies pursuing regulatory approval of a variety of compounds, mostly in Europe and the USA.

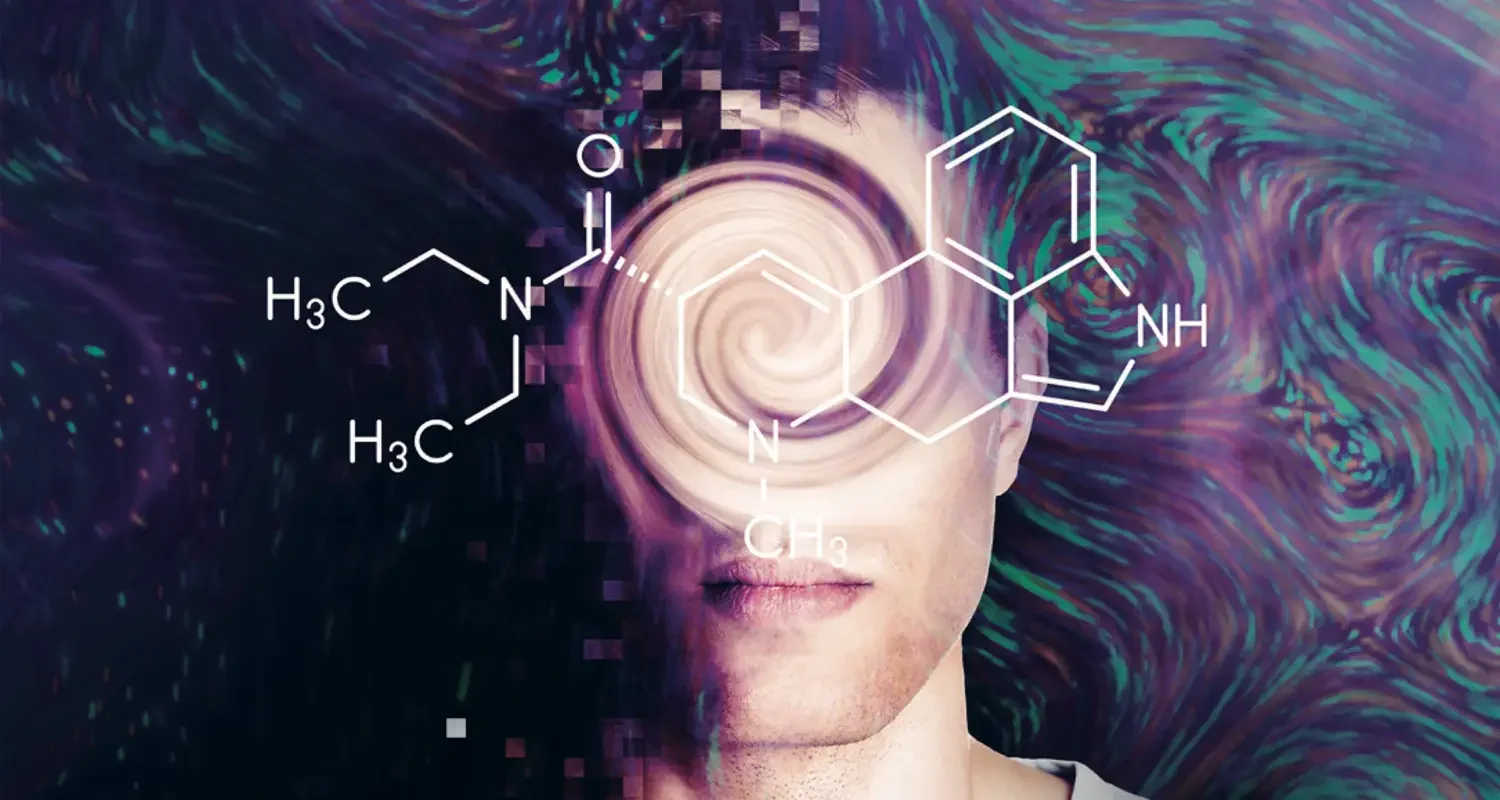

This activity has led to the so-called “classic psychedelics” (LSD, psilocybin, DMT and mescaline) and a series of closely related chemical analogues (MDMA, ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT, among many others) being examined in pre-clinical and clinical studies. Results so far have been very encouraging, with few serious adverse events and promising efficacy data for PTSD, depression, substance use disorders and many other conditions.

However, there continues to be stigma around this research, given the many pejorative connotations of “psychedelic”. Psychedelics remain associated in the public eye with illicit drug use and are widely perceived as risky and harmful. That is a policy misclassification with little basis in the scientific evidence to date, which spans a wide range of study designs and approaches, ranging from anthropology to medicine, toxicology and sociology. The classic psychedelics are in fact known to present very little toxicity to the human organism, being safe for use under medical and/or psychotherapeutic supervision. Furthermore, they are not strongly linked with abusive patterns of consumption and do not lead to drug dependence. There is, however, the potential for abuse in terms of excessive frequency and/or dosage — a risk factor which must be taken into consideration, just as for many other pharmaceuticals.

Most studies are done under carefully controlled clinical settings, with professional supervision during the entire duration of the effects. The treatment progresses in cycles, with each cycle typically beginning with a preparatory psychotherapy session, followed by a medication session. This is when a psychedelic substance is administered to the patient, continuously accompanied by specifically trained professionals, generally lying down with eyes closed, perhaps listening to instrumental music, for long periods of time. Talk therapy may be included at various points. After each psychedelic session, more psychotherapy sessions, this time without administration of any substance, are conducted to close each cycle. Protocols differ in many aspects, but this basic and cyclic structure is an important commonality.

While a range of different approaches have already been assessed, there remains much that requires further investigation to safely and responsibly move forward. Psychedelics, by their nature, induce altered states of consciousness, which can for many participants, become some of the most meaningful experiences of their lives. That raises ethical questions deserving of the most serious consideration. Guiding patients through the process also requires specialist training; scaling this training up to the levels needed to meet demand requires educating many thousands of practitioners in the coming years. And commercialisation of these substances may be challenging in a healthcare marketplace which is ill-prepared for the overall structure and intensive care required for a safe and effective course of treatment.

While the formalisation of psychedelic medicine continues, we must also recognise that the properties of many such compounds have been known for millennia and are still utilised by indigenous peoples, the most well-known examples being ayahuasca, peyote and mushrooms. Further insights are likely to be found by working with these peoples and discoveries to be made in ethical and fair collaboration. There are thus concerns to be addressed around intellectual property, which is currently booming, and social justice. If the nascent industry of psychedelic compounds and treatments is to grow ethically, it must take up the challenge of developing models which are inclusive of tangible and intangible indigenous knowledge. This may also create an opportunity to prevent mental health issues, by respecting indigenous sovereignty, biodiversity and land rights, all of which are currently threatened by climate change.

For our societies to fully benefit from the exciting advances now being made in psychedelic medicine, policymakers and stakeholders need to pay attention and dedicate appropriate levels of resources to this important field. Unsubstantiated obstacles to research with currently controlled substances should be loosened. And diverse and inclusive special groups must be convened to discuss how these therapies can be deployed in ways that respect the United Nations’ “right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its application” (REBSP), as well as treaties such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Nagoya Protocol.

These are all urgent and fundamental to safeguard the ethical and responsible maturing of this field. The specific combination of psychedelic drug with therapy, which does not easily fit into current prescription and dispensing of psychiatrics medications for daily use at home, merits particular attention. Indeed, there may be profit incentives for pursuing such models which are likely to be risky and harmful for many. Therefore, in addition to rigorous scientific research, respect and reparation with indigenous peoples, we need democratic and diplomatic action to safely adjust our healthcare infrastructure, education and practice in order to implement these new treatments in the 21st century. This time, we hope the psychedelic promise will not be allowed to fail.

1 Robin L. Carhart-Harris et al., 'Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging’, PNAS 113 4853 (2016), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518377113.