It may not attract much attention in everyday life, but the fungal kingdom has a remarkable breadth and depth of impact on human and environmental well-being.

Fungi are integral to health, agriculture, biodiversity, ecology, manufacturing and biomedicine. They are Earth’s pre-eminent degraders of organic matter, are among the best-characterised model systems for biomedical research and produce enzymes crucial for fermentation, food production, bioremediation and biofuel production. Fungi have also made invaluable contributions to medicine: they produce a phenomenal diversity of chemicals that we have found uses for as antibiotics, immunosuppressants that make organ transplants possible and drugs that reduce the risk of heart disease.

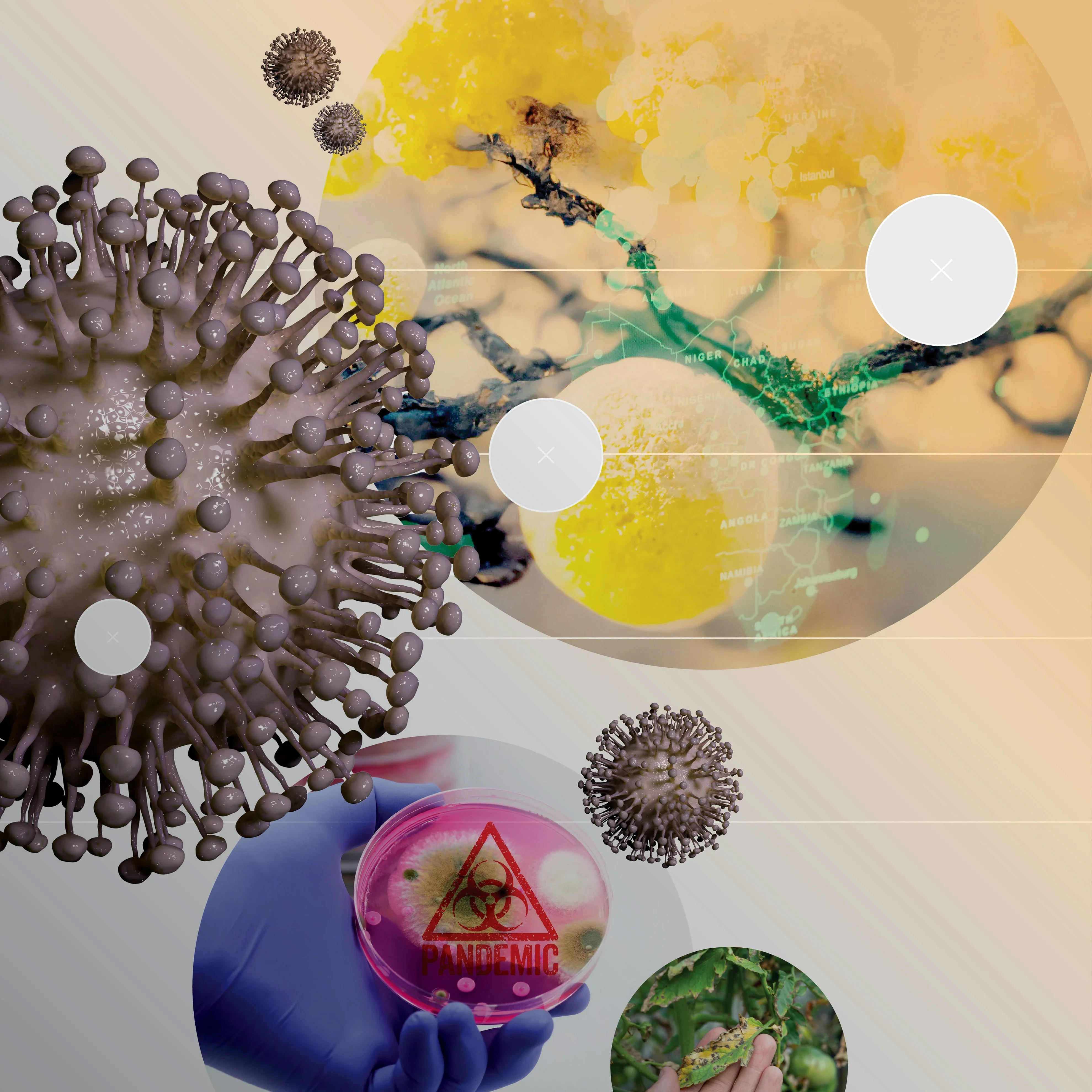

But while there is still much to be learned about the potential benefits of fungi, they also have detrimental aspects that need to be addressed. Novel infectious diseases caused by fungi are on the increase all over the world, just as they are for other microbes (such as zoonotic viruses) — but fungi are responsible for an increasing proportion of emerging-disease alerts across humans, plants and animals, possibly because as eukaryotes they are more closely related to their host animals and plants than bacteria or viruses are, and thus more difficult to treat. This has grave consequences:

Fungi have a staggering impact on human health. Of an estimated 6 million species of fungi, more than 200 are closely associated with humans. They may live on us harmlessly, form part of our microbiome or, as pathogens, cause infectious and sometimes lethal diseases. These pathogens (including Candida, Aspergillus, and Cryptococcus species) currently infect billions of people worldwide and cause more than 1.5 million deaths per year — on a par with prominent bacterial and protozoan pathogens, such as those that cause tuberculosis and malaria.1

Fungi are a serious threat to global food security. Crop-destroying fungi have been a threat to humanity since the agricultural revolution. Diseases caused by fungi and oomycetes have led to the starvation of populations, ruination of economies and decimation of landscapes. Such diseases have been increasing in severity since the mid-20th century: emerging fungal diseases now pose an unprecedented threat to global food security and ecosystem health,2 by causing epidemics in staple crops that feed billions and producing toxins that contaminate food supplies and cause cancer. The future will bring new variants of old foes, movement of old adversaries to new areas and entirely new fungal diseases.3 Further, there is alarmingly open scope for fungi and their toxins to be deployed as biological weapons.

Fungi cause rapid species extinctions and loss of biodiversity. It is unlikely that there is a single animal on the planet that has not been parasitised by fungi, and animals are also subject to novel and re-emerging diseases. Several fungal species have recently become notorious for causing emerging infectious diseases which have led to massive die-offs, population declines and, in some cases, species extinctions. For example, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) and B. salamandrivorans (Bsal) cause devastating skin infections in amphibians. Bd has contributed to the decline of 6.5 per cent of amphibian species — the greatest documented loss of biodiversity attributable to any one pathogen.4 Pseudogymnoascus destructans causes white-nose syndrome, which has killed millions of North American hibernating bats: mortality can exceed 90 per cent. We have historically been concerned about the emergence of novel diseases from wildlife reservoirs, but novel disease also threatens wildlife conservation and ultimately global biodiversity.

The fundamental challenge in tackling these problems associated with fungi — which is also the fundamental challenge when it comes to harnessing their enormous potential benefits — is to understand the unique facets of their biology that are responsible for their remarkable properties. Currently, science is at an inflection point and uniquely positioned to dramatically accelerate the pace of discovery, thanks to advances in genomics, genetics and the identification of pathogens. However, this acceleration is contingent upon bridging the gaps between research focusing on humans, plants and wildlife. These have traditionally been disparate disciplines, and while there have been seminal discoveries within each, it is now exquisitely clear that an interdisciplinary approach is crucial because solving these challenges is multi-faceted, necessitating a One Health Perspective. We have yet to leverage fundamental discoveries on novel targets required for fungal stress survival to develop a new class of antifungal drug (it has been over 20 years since the last new class was introduced), to develop a vaccine to prevent fungal disease or to develop a resistance-evasive strategy to protect crops from devastating pathogens. That could change if the science focuses on:

- Understanding the forces driving the emergence, evolution and spread of fungi including the integration of mathematical models, genetics, genomics and population biology at multiple temporal and spatial scales.

Identifying mechanisms of fungal adaptation and interactions with hosts and other microbes by understanding microbiomes and interspecies interactions through genomic analysis and other approaches, including novel types of tissue, organoid and animal models.

- Understanding the evolution of resistance to fungicides and antifungals across the fungal kingdom, including field studies to understand where, how and why resistance develops in agricultural fields, composting and in patients.

- Developing novel strategies to thwart fungal disease including chemical genomics, functional genomics, experimental evolution, small-molecule and natural product screening, and, ultimately, structure-guided drug design.

Addressing these challenges successfully over the next 5 to 10 years could have major implications for the planet. In the context of global health, it is estimated that 1.6 million lives could be saved; in the context of agriculture, sufficient food could be salvaged to support over 8 per cent of the world’s population; and in the context of biodiversity, new treatment and protective strategies could be developed alongside agricultural practices that would minimise crops’ vulnerability to fungal pathogens.

Better understanding the fungal kingdom would contribute to addressing some of humanity’s and the planet’s grandest challenges. Fungi could solve the world’s plastic crisis by targeted degradation both in the environment and in recycling and treatment plants; better control of fungal pathogens that affect trees would increase the biomass available for the absorption of CO2 and better understanding of the role of fungi in our own bodies could help us tackle widespread and persistent health issues such as autoimmune disorders and gastrointestinal conditions. The challenges posed by fungi are significant and urgent; the benefits they offer are too.