This would represent an extraordinary investment of technical and commercial resources, mandated by the urgency of climate change. However, the deep seabed is one of the most poorly understood of all the earth’s environments. Thus, there is also a significant risk that such mining may severely harm a part of the environment that has so far escaped harm from humanity — and that harm could last for thousands of years. We are therefore confronted with a unique tension between two environmental goods.

Deep-sea mining has been the subject of multi-national debate since the 1960s, when it was thought that it might provide a solution to the perceived problem of diminishing terrestrial resources. Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) feared that this activity would be led by wealthy industrialised nations which more easily develop the technological capacity to conduct these activities, “making the rich richer and the poor poorer” in the words of Arvid Pardo, then Malta’s ambassador to the UN. This debate, in which Pardo played a key role, resulted in a fundamentally permissive legal regime for deep-sea mining, included in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – also referred to as the “constitution for the ocean”.

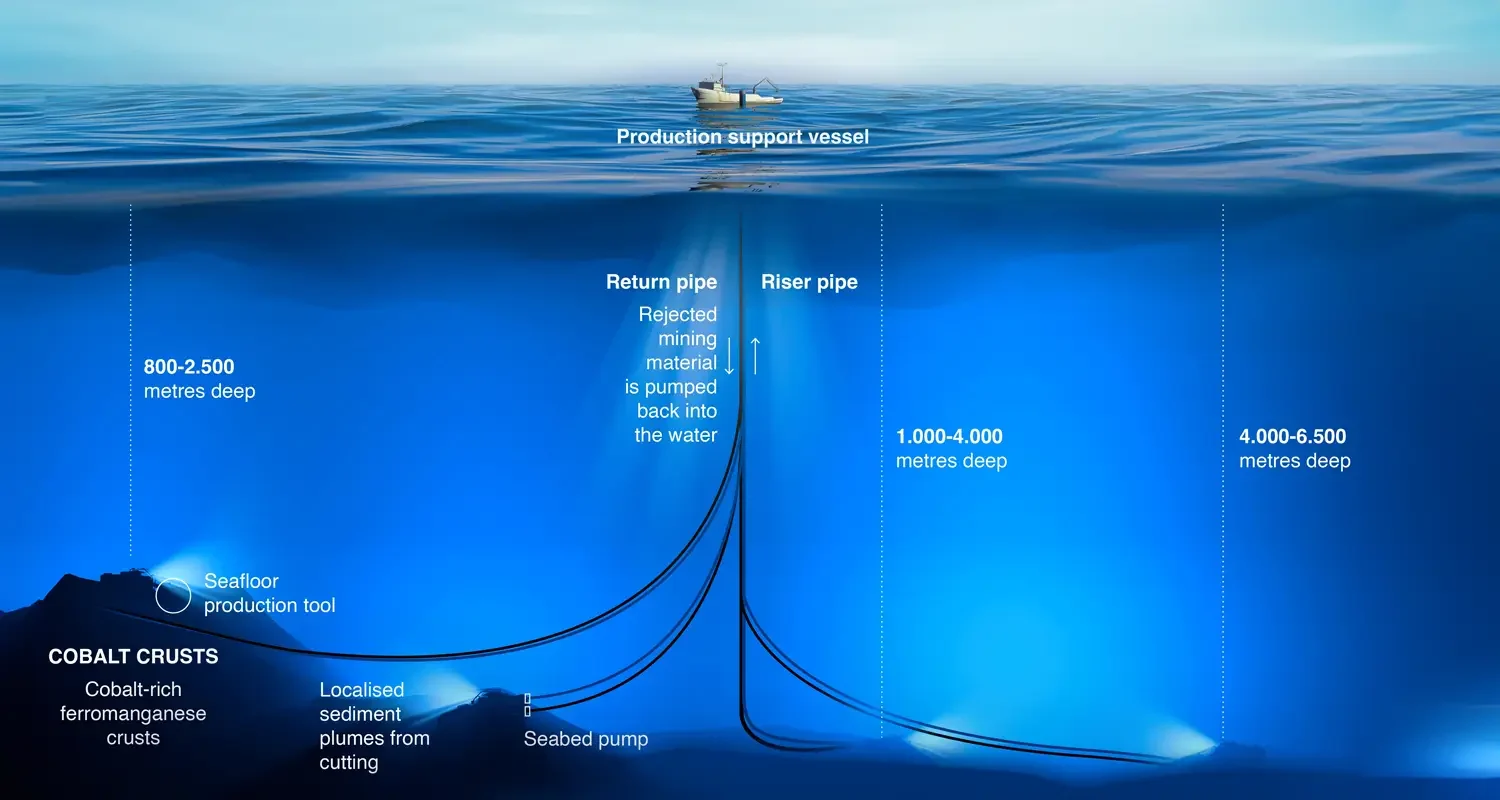

This was one of the first attempts to create a truly fair and just regime for a global common, namely the mineral resources of the deep seabed and the seabed as such, deep-sea mining, based on benefit- and technology-sharing. However, terrestrial resources turned not to be running out after all, so the issue lay dormant for several decades. Now, however, it is back at the centre of the international agenda. Demand for raw materials such as lithium, cobalt and other resources required for wind turbines, solar panels and other renewable energy infrastructure essential for the green energy transition, is rising fast. Three classes of deep-sea deposits – polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts – have attracted particular commercial interest due to their enrichment in metals such as nickel, cobalt, copper, titanium and the rare earth elements needed for lithium-ion batteries. However, many anticipate that mining for these deposits poses such large environmental risks as to throw into question whether it should be allowed at all.

Crucially, we do not have a robust factual basis for the environmental risks of deep seabed mining. After all, many renewable energy technologies have environmental impacts. For example, the erection of offshore wind turbines damages the habitats of otherwise highly protected species such as harbour porpoises and seals. Terrestrial mining for key metals and minerals can itself cause serious environmental degradation and social injustices. We accept these downsides because we believe the benefits are greater. However, scientists predict that the effects of deep seabed mining activities today will have repercussions for thousands of years in the future — possibly even longer, since polymetallic nodules take 1 million years to form, putting associated ecosystems at significant risk of extinction.1 Identifying an acceptable level of environmental risk, or indeed whether there is any acceptable level, is the single biggest challenge of this debate.

To meet this challenge, we need more research into the environmental effects of deep seabed mining. There are three broad areas that require investigation. First, we need to understand the effects of mining on the relationship between deep seabed fauna and the polymetallic nodules on which they rely. These species have extremely long lifecycles, and don’t easily recover from disturbance. Second, we need to investigate the effect of the changing column of water on the organisms that live on or just beneath the sea floor, and understand their role within the overall climate system. Third, we need to understand how effectively the areas surrounding mining sites can be protected, and how much damage might be done by (for example) the plumes arising from the mining. Is it possible to localise the effect of mining activities, or not?

A few years ago, it seemed that deep-sea mining was an inevitability. However, an increasing number of state and corporate actors have more recently declared their opposition. In 2020/21, French President Macron publicly argued in favour of a complete moratorium on deep seabed mining. Other countries, including Germany, Australia and New Zealand, have called for a “precautionary pause” to allow time for further research on the environmental impacts of mining on deep seabed ecosystems to take place. Some companies have also publicly said they will not (yet) use commodities sourced from the ocean, notably including the auto manufacturers Renault, Volvo, BMW and Volkswagen.

So far, the states that advocate for a precautionary pause and a moratorium seem to be a minority – albeit a growing minority, heavily influenced by NGOs and supported by an increasing number of businesses. It may be that in time a consensus develops that deep-sea mining activity should be significantly constrained or even banned. But as things stand, the International Seabed Authority is called upon to finalise its regulations for deep-sea mining exploitation due to a “two-years-rule” activated by Nauru in 2021. If the exploitation regulations are not agreed upon this summer, the International Seabed Authority must make a decision on the application of Nauru – and potentially also of other States – based on preliminary materials and the terms of the law as it stands. What exactly this standard implies is a matter of considerable legal uncertainty.

This deadline was activated in July 2021 by the Republic of Nauru, and expired in July 2023. Intense discussions led the council of the International Seabed Authority to adopt a decision on a timeline following the expiration of the two-year period, with a commitment to full discussion of marine environmental protection in 2024 and a view to adopting the exploitation regulations in 2025. This outcome was hailed by opponents of deep-sea mining, who welcome it as an opportunity to put an end to the proposals once and for all – but it remains unclear what will happen if further applications are made.

Separately, international negotiations completed in March 2023 also resulted in the formal adoption – on 19 June 2023 – of an agreement on sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. This so-called BBNJ agreement, sometimes called the “High Seas Treaty”, will also be of potential relevance to deep seabed mining as it establishes a minimum standard for conducting environmental impact assessments. It cannot be excluded that this standard will, again, impact the discussions about the environmental standards to be included in the final version of the exploitation regulations of the International Seabed Authority.

It is conceivable that Nauru, or any other state, could choose to go it alone. Once the precedent has been set, others might join it. However, the likelihood of this scenario is arguably minimal, due to widespread acceptance of the framework established by the UN Convention — even by states that have not become party to it, such as the USA. This is a rare example of consensus within international politics; for the moment the debate continues to be conducted within the relevant multilateral fora. The most relevant — and controversial — issue is the question of the specific environmental standards to be included in the ISA exploitation regulations. Furthermore, a debate has evolved around the question on how to prevent the coming into existence of ‘sponsoring States of convenience’, which may be attracted by revenues to accept to sponsor companies from industrialised States without sufficiently caring about the environmental and social standards applied by such companies.

Ultimately, there may not be a single yes or no answer when it comes to deep-sea mining, but rather a multi-level process leading to the formation of a rigid and precautionary legislative basis for such activities. We should accept that the marine environment must be protected, but we might at the same time be forced to accept that deep-sea mining of certain minerals, or in certain areas, may turn out to be unavoidable to fend off the worst of climate change. Thus, we should seek a balanced approach to deep-sea mining, with regulation based on as much well-informed science as possible. Ideally, we would use the years to come to conduct an intensive research programme before embarking on any deep-sea mining activities. We should also fully consider the potential for alternatives, such as greater utilisation of terrestrial mining.

In conclusion, we depend on a multifaceted strategy which reluctantly accepts that difficult decisions may need to be taken over deep-sea mining. A potential broader outcome is that – where unavoidable and complementary approaches are not possible – a balance between remediation of the climate and protection of the marine environment needs to be found. We need to inform these decision-making processes to the greatest extent possible by advocating for better scientific evidence, making decision on the basis of that evidence, and negotiating internationally in good faith.

1 Craig R. Smith et al., ‘Deep-Sea Miscnceptions Cause Under-Estimation of Seabed-Mining Impacts’, Science and Society 35: 853 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.07.002.